Featured

Verified Paypal Account (USA)

Get Your Verified PayPal Account Today! Unlock the full potential of PayPal with a completely ver..

Reloadable Virtual Credit Card

Unlock Unlimited Freedom with Our Reloadable Virtual Credit Card! 💳💥 Say goodbye to limits and he..

Paypal VCC

Transform Your PayPal Experience with Our PayPal VCC! 💳🚀 Unlock the full potential of your PayPal..

Virtual US Bank

Verify your US PayPal account with our virtual bank. Our bank can work under any name associated wit..

Verified Business Wise Account

🔥LIMITED OFFER: Buy Your Business Wise Account TODAY and Unlock Global Financial Freedom! 🌍💸 Are ..

Verified Payoneer Account

🚀 Unlock Global Earning Potential with Your Own VERIFIED Payoneer Account! 🌐💸 Dreaming of effortl..

Dedicated US IP Address

Unlock Unlimited Freedom with Your Own Dedicated US IP Address! 🌐 Imagine having your very own sl..

Dedicated UK IP Address

Unlock the Power of a Dedicated UK IP Address! 🇬🇧 Take control of your online experience with a D..

WHMCS Lifetime License - Full Ownership

Unlock the full potential of your web hosting business with our WHMCS Lifetime License. This license..

Cheap cPanel License (VPS)

Get the power of cPanel at an unbeatable price with our Cheap cPanel License. Designed for budget-co..

Get Your Own Custom Website Created for Just $250 - No Experience Needed!

Professional Website Creation Service – Custom, Affordable, and SEO-Friendly Looking for a stunni..

🔥 Skyrocket Your Business with a Google Ads Account Loaded with $1000 - Instant Start & Free Replacement! 🚀

Unleash the power of Google Ads with our premium account, preloaded with a whopping $1000 balance! W..

🚀 Get Your Custom Driver's License Online – Instant Verification for All Your Needs! 🚀

Why wait in long lines or deal with the hassle of traditional processes when you can buy a driver's ..

Paxful Verified Account

Unlock Unlimited Earning Potential with a Verified Paxful Account! 🔥💰 Don’t waste time with unverif..

Zellepay Account

Are you looking to buy ZellePay Verified Account quickly and securely? Look no further! ..

Verified UK PayPal Account

Get a fully Verified UK PayPal Account with instant access to secure online transactions, sending an..

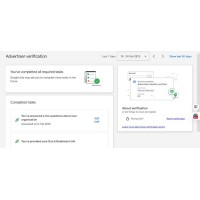

Google Ads Account Verification

Ensure seamless approval and compliance with our Google Ads Verification Service. Our expert team he..

Google Ads Account

Kickstart your online marketing campaigns with our Google Ads Account, fully verified and ready to u..

Google Ads Account Business Operation Verification Service

Ensure smooth ad campaigns with our Google Ads Account Business Operation Verification Service. We h..